Summary

The World Health Organization (WHO) has faced growing criticism for fostering an unsafe, untransparent, and unfair working environment. Allegations include mishandling whistleblowing complaints, suppressing scientific reports, allowing conflicts of interest to influence its decisions, and promoting experts with financial stakes in WHO guidelines. These issues have raised concerns about the integrity and accountability of the organization, particularly in its work on global health guidelines related to transgender care.

Background/Context

The WHO has been at the forefront of global public health for decades, but in recent years, internal issues have surfaced that call into question its governance and organizational culture. Allegations of cronyism, retaliation against whistleblowers, and the suppression of crucial health reports have sparked widespread concern[1]. In 2020, WHO published a report on Italy’s pandemic preparedness that was withdrawn after it revealed flaws in Italy's approach to COVID-19[2]. This suppression was linked to potential conflicts of interest, with senior officials allegedly pressuring researchers to modify findings[3].

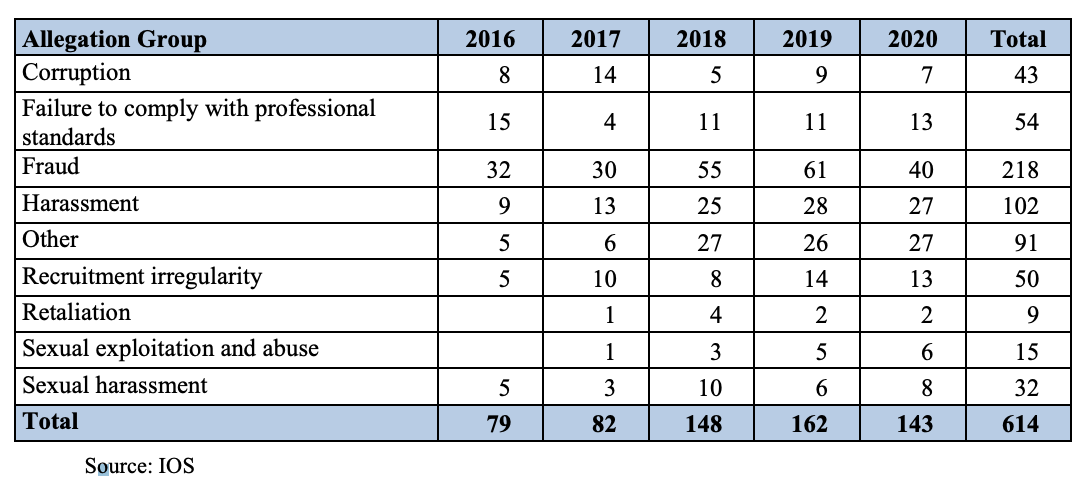

In parallel, there has been a significant increase in complaints of misconduct within the organization, particularly from staff about harassment, fraud, and sexual misconduct[4]. These issues have been exacerbated by WHO's apparent failure to effectively address such complaints, with several whistleblowers reporting retaliation after raising concerns. Transparency International and other organizations have called for reform to protect whistleblowers and ensure the organization's accountability[5].

Relevant WHO Policy/Action

WHO has established policies to handle internal complaints, including those of misconduct and conflicts of interest, through its Office of Compliance, Risk Management, and Ethics (CRE)[6] Cases that require further investigation are referred to the WHO Internal Oversight Service (IOS)[7]. The organization also has an Ethics Office to address ethical issues and conflicts of interest within its staff. Despite these policies, concerns have been raised about the organization’s failure to implement them effectively, particularly in cases involving retaliation against whistleblowers or the suppression of key scientific reports[8].

The WHO also has internal oversight mechanisms intended to monitor staff behavior and ensure transparency. However, external audits have revealed that the number of complaints against WHO staff, including serious issues like fraud and sexual harassment, has increased significantly in recent years. In response to these findings, WHO has been urged to strengthen its internal oversight systems and improve its whistleblower protection policies[9].

Legal or Regulatory Violations

WHO’s handling of whistleblower complaints and misconduct cases may violate international labor standards, including the United Nations Convention Against Corruption and International Labour Organization (ILO) standards on protecting workers' rights[10]. Allegations of retaliation and the suppression of scientific research also raise ethical and legal concerns, potentially breaching WHO’s own policy on preventing and addressing retaliation, which are designed to safeguard staff from discrimination and harassment[11].

Additionally, the appointment of experts with financial stakes in gender-affirming care raises concerns about conflicts of interest, which could violate WHO’s standards for impartiality and transparency in its guidelines. Such practices may also undermine the organization’s credibility and impartiality in developing evidence-based health policies[12].

Consequences/Impact

The lack of transparency and accountability at the WHO has had significant consequences for both the organization’s credibility and its effectiveness. The suppression of scientific reports, such as the 2020 Italy pandemic preparedness report, raises questions about the WHO’s commitment to transparency and its ability to make evidence-based decisions. Furthermore, the growing number of complaints about misconduct, including harassment and fraud, has highlighted systemic issues that affect the credibility of the organization[13].

The conflict-of-interest allegations related to the transgender healthcare guidelines have also led to concerns about the impartiality of WHO's medical recommendations. The organization's ability to set global health standards is increasingly questioned, as critics argue that financial ties to the industries promoting gender-affirming care may cloud decision-making and harm public health outcomes[14]. Calls for reform, particularly in the areas of internal oversight, whistleblower protection, and conflict-of-interest management, have intensified as the organization faces heightened scrutiny.

Relevant Documents

- Report of the External Auditor on WHO’s working conditions

- Whistleblower Protection United Nations Advocacy Report

- WHO Abuse Content Policy

- WHO Office of Internal Oversight Services

- WHO Policy on Preventing and Addressing Retaliation

- UN Convention against Corruption- UNCAC

- International Labour Organization Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work and its follow-up

Relevant Commentary

- Transparency International on WHO's working environment

- Transparency International on Whistleblower protection at the United Nations

- The LGBT Courage Coalition's Accusations of Conflicts of Interest

- Whistleblowing International Network, Open Letter to the 74th World Health Assembly.

- Whistleblower claims WHO tried to force him to change report about Italy’s pandemic protocols

References

- ↑ For Example: Cronin, E. A., Afifi, A., & Unit, J. I. (2018). Review of whistle-blower policies and practices in United Nations Sytem organizations /: prepared by Eileen A. Cronin and Aicha Afifi, Joint Inspection Unit. United Nations Digital Library System.

- ↑ Ramsay, S. (2021, 14 april). COVID-19: Whistleblower claims WHO tried to force him to change report about Italy's pandemic protocols. Sky News.

- ↑ Transparency International. (2022, 23 juni). UN agencies are failing whistleblowers: The case of the WHO whistleblower - Blog. Transparency.org.

- ↑ General Of India, O. O. T. C. A. A. & Mr. K. Subramaniam. (2021). Report of the External Auditor. In SEVENTY-FOURTH WORLD HEALTH ASSEMBLY.

- ↑ Open Letter to #WHA74: Support COVID-19 whistleblower Dr. Zambon - Whistleblowing International Network. (z.d.).

- ↑ ‘WHO Policy on Preventing and Addressing Abusive Conduct’ (2023)

- ↑ ‘Office of Internal Oversight Services’ (2025).

- ↑ Maslen, C. (2021). Whistleblower protection at the United Nations.

- ↑ General Of India, O. O. T. C. A. A. & Mr. K. Subramaniam. (2021). Report of the External Auditor. In SEVENTY-FOURTH WORLD HEALTH ASSEMBLY.

- ↑ ‘Full Text of the UN Convention against Corruption – UNCAC | UNCAC Coalition’ ; ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work and its follow-up. (2022). International Labour Organization.

- ↑ Ethics Unit of the Department of Compliance, Risk Management and Ethics, Office of Internal Oversight Services, Department of Human Resources and Talent Management & Ethics Unit, Internal Oversight Services, and HR Policy Coordination and Internal Justice. (2023).

- ↑ Reinl, James, ‘UN trans health panel accused of CRONYISM: 80% of WHO’s “experts” flagged for conflicts of interest...’, Mail Online (3 February 2024)

- ↑ General Of India, O. O. T. C. A. A. & Mr. K. Subramaniam. (2021). Report of the External Auditor. In SEVENTY-FOURTH WORLD HEALTH ASSEMBLY.

- ↑ Reinl, James, ‘UN trans health panel accused of CRONYISM: 80% of WHO’s “experts” flagged for conflicts of interest...’, Mail Online (3 February 2024)