Summary

The World Health Organization (WHO), founded in 1948 to promote global health equity, has faced significant criticism for its response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Allegations of undue Chinese influence and operational shortcomings have fueled debates about its effectiveness and impartiality. Under Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the WHO has been accused of praising China's outbreak management while delaying critical actions, such as declaring COVID-19 a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC). Critics argue this approach undermined global efforts to curb the virus and revealed vulnerabilities in WHO's reliance on voluntary funding from member states, including increasing financial and political support from China.

Background/Context

The WHO has historically played a vital role in combating communicable diseases and enhancing global health infrastructure. However, the COVID-19 pandemic exposed cracks in the organization’s operations and governance.

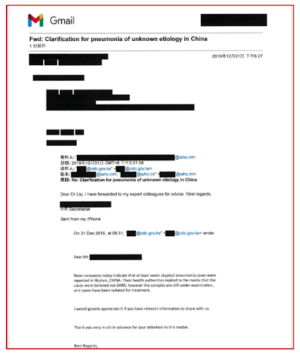

In contrast to the WHO's criticism of China's lack of transparency during the 2003 SARS outbreak, Dr. Tedros praised China's "commitment and transparency" in 2020, despite mounting evidence of censorship and initial mishandling of the outbreak in Wuhan.[1] China suppressed early warnings from doctors, delayed reporting the human-to-human transmissibility of the virus, and underreported cases.[2] These actions likely delayed the global response.[3]

Adding to the criticism, Taiwan—a key player in global health—has been excluded from WHO decision-making bodies since 2016, under pressure from China.[4] This exclusion has left Taiwan vulnerable to delays in critical health information. According to researchers, Taiwan’s inability to access WHO resources also represents a significant gap in global health preparedness.[5]

Relevant WHO Policy/Action

- Delayed Declaration of PHEIC WHO delayed declaring a PHEIC despite acknowledging the severity of the outbreak in China on January 23, 2020.[6] Critics argue this delay, compounded by WHO’s initial deference to Chinese claims, allowed COVID-19 to spread exponentially worldwide.[7] Notably, WHO refrained from publicly challenging Chinese data, which reportedly omitted many asymptomatic and mild cases. WHO experts, including epidemiologist Bruce Aylward, echoed Beijing’s claims of transparency despite substantial evidence to the contrary.[8] According to the Action Review of the COVID-19, this delay indicated the pressure of the Chinese Communist Party.[9]

2. Taiwan’s Exclusion The exclusion of Taiwan from WHO activities—driven by China's "One China" policy—has significantly hampered global health coordination. Especially since the WHO’s Director-General reiterated this policy.[10] Due to this biased approach Taiwan was not able to share its early warnings about COVID-19 with the organization in a timely manner. [11]This indicates that the WHO’s alignment with Beijing undermindes the principles of universal health coverage and global health equity.[12]

3. Financial Dependence and Influence WHO’s reliance on voluntary contributions, which grew to $4.7 billion in 2018-19, has made it susceptible to political pressures. While the U.S. remains the largest donor, China's contributions have risen by 52% since 2014. Beijing’s increased funding has coincided with its growing influence within the organization. Observers note that this financial dependency may have influenced WHO’s reluctance to confront China’s early mismanagement of the outbreak.[13]

Legal or Regulatory Concerns

While no direct legal violations have been identified, WHO’s actions have raised questions about its adherence to its constitution, which mandates impartiality and transparency. The exclusion of Taiwan contradicts the WHO’s commitment to health equity and undermines international pandemic preparedness.

Consequences/Impact

- Damage to WHO’s Credibility WHO’s perceived alignment with Chinese interests has diminished its reputation as a neutral global health authority. According to Michael Collins of the Council on Foreign Relations, this may erode trust in the organization’s guidance during pandemics.[14]

- Global Public Health Risks The delay in declaring a PHEIC and uncritical acceptance of Chinese data contributed to the rapid global spread of COVID-19. By the time WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic on March 11, 2020, the virus had already established footholds in multiple countries, wasting 6 weeks of global response.[15]

- Taiwan’s Vulnerability Without direct WHO support, Taiwan has faced challenges in accessing real-time outbreak information, leading to potential gaps in its pandemic response.[16] Despite these challenges, Taiwan managed an effective containment strategy, raising questions about the fairness and efficacy of its exclusion.[17]

Relevant Documents

- Ministry of Health and Welfare, statement on Taiwan’s Exclusion from the WHA.

- WHO Press release praising China’s policy

- AFTER ACTION REVIEW OF THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC: The Lessons Learned and a Path Forward.

- COVID-19 PHEIC declaration on the 30th of January

- WHO Universal Health Coverage Definition

- WHO Health Equity

Relevant Commentary

- Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness: Taiwan’s successful COVID-19 mitigation and containment strategy: achieving quasi population immunity

- China asked WHO to cover up coronavirus outbreak: German intelligence service

- Council on Foreign Relations: Analysis of WHO’s COVID-19 response and implications of Chinese influence.

- How WHO Became China’s Coronavirus Accomplice

- Newly elected WHO chief reiterates one-China principle

References

- ↑ Press Release WHO. (2020, 28 januari). WHO, China leaders discuss next steps in battle against coronavirus outbreak. World Health Organization. https://web.archive.org/web/20250115191929/https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/28-01-2020-who-china-leaders-discuss-next-steps-in-battle-against-coronavirus-outbreak

- ↑ AFTER ACTION REVIEW OF THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC: The Lessons Learned and a Path Forward. (2024). In Select Subcommittee On The Coronavirus Pandemic Committee On Oversight And Accountability. U.S. House of Representatives. https://oversight.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/2024.12.04-SSCP-FINAL-REPORT-ANS.pdf

- ↑ AFTER ACTION REVIEW OF THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC: The Lessons Learned and a Path Forward. (2024). In Select Subcommittee On The Coronavirus Pandemic Committee On Oversight And Accountability. U.S. House of Representatives. https://oversight.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/2024.12.04-SSCP-FINAL-REPORT-ANS.pdf

- ↑ Collins, Michael, ‘The WHO and China: Dereliction of duty’, Council on Foreign Relations (27 February 2020) <https://www.cfr.org/blog/who-and-china-dereliction-duty>.

- ↑ Collins, Michael, ‘The WHO and China: Dereliction of duty’, Council on Foreign Relations (27 February 2020) <https://www.cfr.org/blog/who-and-china-dereliction-duty>.

- ↑ ‘COVID-19 Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) Global research and innovation forum’ (2025) ‘COVID-19 Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) Global research and innovation forum’ (2025) https://web.archive.org/web/20250102035457/https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-public-health-emergency-of-international-concern-(pheic)-global-research-and-innovation-forum

- ↑ AFTER ACTION REVIEW OF THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC: The Lessons Learned and a Path Forward. (2024). In Select Subcommittee On The Coronavirus Pandemic Committee On Oversight And Accountability. U.S. House of Representatives. https://oversight.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/2024.12.04-SSCP-FINAL-REPORT-ANS.pdf

- ↑ Feldwisch-Drentrup, Hinnerk, ‘How WHO became China’s accomplice in the coronavirus pandemic’, Foreign Policy (3 April 2020) <https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/04/02/china-coronavirus-who-health-soft-power/>.

- ↑ AFTER ACTION REVIEW OF THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC: The Lessons Learned and a Path Forward. (2024). In Select Subcommittee On The Coronavirus Pandemic Committee On Oversight And Accountability. U.S. House of Representatives. https://oversight.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/2024.12.04-SSCP-FINAL-REPORT-ANS.pdf

- ↑ 刘小卓, ‘Newly elected WHO chief reiterates one-China principle - World - Chinadaily.com.cn’ <https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/world/2017-05/25/content_29490343.htm>.

- ↑ AFTER ACTION REVIEW OF THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC: The Lessons Learned and a Path Forward. (2024). In Select Subcommittee On The Coronavirus Pandemic Committee On Oversight And Accountability. U.S. House of Representatives. https://oversight.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/2024.12.04-SSCP-FINAL-REPORT-ANS.pdf

- ↑ World Health Organization: WHO, ‘Universal health coverage (UHC)’ (2023) <https://web.archive.org/web/20250115202240/https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/universal-health-coverage-(uhc)>; World Health Organization: WHO, ‘Health equity’ (2021) <https://web.archive.org/web/20250115202439/https://www.who.int/health-topics/health-equity#tab=tab_1>.

- ↑ Collins, Michael, ‘The WHO and China: Dereliction of duty’, Council on Foreign Relations (27 February 2020) <https://www.cfr.org/blog/who/who-and-china-derelicteliction-duty>

- ↑ Collins, Michael, ‘The WHO and China: Dereliction of duty’, Council on Foreign Relations (27 February 2020) <https://www.cfr.org/blog/who-and-china-dereliction-duty>.

- ↑ ‘China asked WHO to cover up coronavirus outbreak: German intelligence service | Taiwan News | May. 9, 2020 19:53’ (2020) <https://www.taiwannews.com.tw/news/3931126>.

- ↑ 國際合作組, ‘The Statement on Taiwan’s Exclusion from WHA- Ministry of Health and Welfare’ <https://www.mohw.gov.tw/cp-4638-53985-2.html>.

- ↑ Chien, Li-Chien, Christian K. Beÿ and Kristi L. Koenig, ‘Taiwan’s successful COVID-19 mitigation and containment strategy: achieving quasi population immunity’, Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 16 (2020) 434–437 10.1017/dmp.2020.357>.